Carbohydrate, Pigment, and Enzyme Analyses Indicate Raw Lycopersicon esculentums are More Nutritious than their Boiled Counterparts

by Erik Bailey, Jamie Crimmins, Josh Mastenbrook, Kathy Ong, and Xinh Pham

ABSTRACT

Contrary to popular belief, it was found that boiled and raw Lycopersicon esculentum differ in chemical composition; raw tomatoes offer a greater nutritional value, based on lycopene (an anti-oxidant-containing pigment in the tomato) content. Several tests were performed to investigate whether boiled tomatoes are more nutritious than raw tomatoes. To analyze the tomatoes' sugar contents, the Benedict's, Barfoed's, Selivanoff's, Bial's, and Iodine tests were performed. It was found that both tomatoes contained monosaccharides including ketoses, reducing sugars, and furanose rings. A paper chromatography test was performed to determine the pigment identity for both raw and boiled tomatoes. The samples had the same rate of flow and had an orange tone, which means that they both contained the pigment carotene. Catechol, which oxidizes when catalyzed by polyphenoloxidase (PPO), was used to test for the presence of PPO in both tomatoes, yet neither contained PPO. pH values were also analyzed for both raw and boiled but no difference was found. Through the Bradford Protein Assay, it was concluded that the boiled tomato (0.903 mg protein / g tomato), contained more protein than the raw tomato which had 0.905 mg protein / g tomato. Also, through spectrophotometry, calculations found that the raw tomato contained 0.66810 microgram lycopene / g tomato compared to 0.63987 micrograms lycopene / g tomato for the boiled.

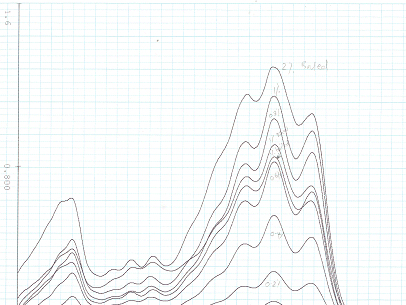

Figure 1. Absorption reading of lycopene. Peaks show the maximum absorption of the different dilutions of the lycopene solution from the tomato lycopene pill. This standard was used to calculate the amount of lycopene in the raw and boiled tomatoes in micrograms per gram of tomato sample.

DISCUSSION

In this investigation, we set out to verify that boiled tomatoes are healthier than raw tomatoes. We conducted three types of experiments to determine which is more nutritious. According to a publication in the Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry , when boiled, a tomato's antioxidants, specifically lycopene, are released, making them more beneficial to one's health (Dewanto et.al., 2002). Extrapolating, this indicates that a characterization of the nutritional value of a tomato can be based, in part, on its lycopene concentration. After conducting our investigation, we found that our data did not support our hypothesis that boiled tomatoes are better for one's health than raw tomatoes, based on carbohydrate, pigment, and enzyme analyses, with a focus on lycopene concentration differences.

The first experiment was a qualitative examination of the carbohydrate content of a raw and boiled Lycopersicon esculentum involving five different tests. The first test was Benedict‘s test, which is used to determine whether or not a reducing sugar is present, signaled by the formation of a precipitate and an orange/red color charge of the solution (Krha et. al., 2003). All of our samples had a significant color change, with no visual color or precipitate amount differences between the raw and boiled tomato solutions (Figure 6). This indicates that at least one reducing sugar was present in each of the samples, but it is not possible with this test alone to specify which reducing sugar(s) was (were) present.

The second test was Barfoed‘s test, which is used to detect monosaccharide reducing sugars, signaled by the formation of an orange/red precipitate (Krha et. al., 2003). All samples yielded precipitate (Figure 5), indicating the presence of at least one reducing monosaccharide specie in each sample. The raw tomato samples however, visually had greater amounts of precipitate (approximately by a factor of three) than the boiled tomato samples (Figure 5c). This observation may be indicative of a greater reducing monosaccharide content of the raw tomato. Because the precipitation is initiated by the reduction of cupric ions by the monosaccharide (Krha et. al., 2003), if a greater amount of reducing monosaccharides was present in the raw sample than in the boiled sample, then one should see more precipitate form in the raw samples. This may be a fair evaluation, as the mass of the raw tomato was 32.04 grams more than the mass of the boiled tomato, thus there is the possibility that some of that mass may contain monosaccharides capable of reducing cupric ions.

The next test performed was Selivanoff‘s test, which is used to test for the presence of ketoses and aldoses, signaled by a time delay in a red hue appearance within the solution. Ketose-containing solutions will show a red hue in less than one minute, whereas aldose-containing solutions gain a red hue after 1.5- 2 minutes (Krha et. al., 2003). All of our samples, boiled and raw, changed to red (Figure 9) in less than one minute, indicating that both tomatoes contained at least one monosaccharide ketose specie; interestingly, the raw sample gained a red hue an average of five seconds faster than the boiled samples (Table 4). Changing red in less time suggests there may have been more ketoses within the raw tomato, as the rate may be dependant upon the concentration of ketoses. If this is true, the implication is that there was a greater concentration of ketoses within the raw tomato. Again, this may be derived from the 32.04 gram mass difference between the raw and boiled tomatoes.

Bial‘s test was then performed to see if furanoses were present. If a furanose ring were present, then a green color change will be apparent (Krha et. al., 2003). In our samples, the raw and boiled tomatoes both returned positive results (Figure 7), but the raw was a darker shade of green (Figure 7c), possibly signifying a higher amount of furanose, again, possibly indicative of the 32.04 gram difference in raw and boiled tomato masses.

Lastly, the Iodine test was performed to test for the presence of starch. The appearance of a bluish-black hue indicates the presence of starch (Krha et. al., 2003). All of the samples returned a negative result, indicating that there was no starch present. Page 128 of the LBS 145 Course Pack suggests that pigments must be removed before a chemical test can be executed to test for the presence of starch (Krha et. al., 2003). Since a major storage center for starch is the fruit (Campbell 2002), the tomato, our observations for the iodine tests are likely misrepresentative of the actual starch content of the two samples. Future tests for starch should be evaluated following the extraction of pigments.

For each test in our carbohydrate experiment, positive, negative and solution only controls were used to ensure that the experimental set-up and reagents were working properly. Additionally, five trials were utilized for each sample, raw and boiled, to reduce possible error, and increase precision.

The results of the tests were opposite to what we had predicted. We believed that we would observe greater amounts of carbohydrates in the boiled tomato sample. We reasoned that heating would result in the cleavage of glycosidic bonds, releasing glucose molecules from disaccharides and polysaccharides. Since glucose is necessary for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), the more bioavailable glucose present, the more ATP that can be manufactured in total by one's cell mitochondria. This would offer more chemical energy for an organism over a period of time, allowing for everyday endergonic processes to take place. We would consider this “healthy.” As noted in the observations above, qualitatively, the raw and boiled tomato samples were nearly identical, with the exception greater color changes, and precipitation amounts for several of the raw samples. Regardless, we feel that the differences we visually observed were significant enough to concluded that the raw tomato would have been healthier compared to the boiled tomato.

According to the USDA Nutrient Database, the average carbohydrate mass of a raw tomato is 4.64 grams, and 5.83 grams for a boiled tomato (Anonymous, 1999). Our observations plainly disagree with this statistic. Several factors may have influenced our results for the carbohydrate experiment. First, the carbohydrate content is a function of an individual tomato. Unless two tomatoes are identical in every form, one cannot make truly fair comparison. To avoid such an error in the future, a significantly larger number of tomatoes should be used, instead of only two. This would increase the probability of a broader representation of the actual tend in carbohydrate concentration. Additionally, a quantitative approach could be taken in the future, possibly utilizing the spectrophotometer to test for color intensity differences (between the raw and boiled samples after executing a specific carbohydrate test), which could be translated into concentrations.

The second set of tests that were conducted had to do with pigment identification and lycopene concentration. Utilizing paper chromatography, we attempted to determine which pigments were present in the skin of a raw and boiled tomato. We believed that the boiled tomato would show more pigments, because research has indicated that thermal processing destroys cell membranes, which may result in the release of pigments not extractable from the raw tomato (Rao and Agarwal, 1999). Unfortunately, the paper chromatography experiment revealed only the presence of carotene in both samples (Figure 13), and the calculated R f values were identical for all trials of both samples (Table 2).

The major problem associated with this test was blatantly obvious from the orange streak, which trailed from the point of application on the chromatography strip to the solvent front. We should have used a longer piece of chromatography paper - which would have allowed for a greater distance for pigment separation to occur, and a mixed (polar/non-polar) solvent such as hexane/acetone - which would have yielded a better separation of the carotenoids due to solubility differences among the pigments.

Our investigation then shifted from a qualitative approach, to a quantitative analysis of lycopene concentrations in the raw and boiled tomatoes. With the aid of an UV spectrophotometer (Figure 10), we were able to produce a lycopene standard curve, and ultimately evaluate the concentrations of lycopene within the raw and boiled tomatoes. We predicted that the boiled tomato would have a greater lycopene concentration than the raw tomato. Recent studies have suggested that heat processing releases lycopene from the tomato. (Dewanto et. al., 2002). The underlying idea is that boiling denatures proteins, thereby altering their conformational shape. Because lycopene is bound up within protein, the conformational change allows the lycopene to become “free.” 1 Our data failed to verify this claim however, as the raw tomato had slightly more lycopene per gram of tomato (Table 5). Interestingly, there was only a 0.028 microgram/ gram tomato difference between the raw and boiled tomato samples. It is difficult to say whether or not this constitutes a significant difference, and we only ran one trial for each tomato sample. Nevertheless, based on research surrounding the health benefits of lycopene (Djuric 2001, Rao and Agarwal, 2000), and our data, we found our prediction to be incorrect; the raw tomato was healthier than the boiled tomato.

Several factors may have altered our results. If we would have used a larger number of tomatoes, and more trials, we would have been able to statistically test (via a t-test) whether or not there was a significant difference between the lycopene concentrations for raw and boiled tomatoes. At minimum, a larger N would have been more representative of the average lycopene concentration, as we were only studying two tomatoes that may have been grown under different conditions, thus adding another factor of uncertainty. Lastly, when we boiled one of the tomatoes, we did not account for the water and matter that had detached from the tomato during the boiling process. Therefore, this may have accounted for or exceeded the relatively small difference in lycopene concentrations between the raw and boiled tomatoes.

The final component of our investigation focused on protein differences between the raw and boiled tomatoes. We first tested for the presence of polyphenoloxidase (PPO), an enzyme found in Lycopersicon esculentums.1 Because biological enzymes function within a specific temperature range, and assuming 100 degrees Celsius exceeds the temperature range of PPO (since tomatoes are not naturally grown at temperatures close to 100 degrees Celsius), we believed PPO would not be present in the boiled sample, but would be found in the raw sample. To our surprise, we detected PPO in neither the raw nor boiled sample (Figure 11). The observation for the boiled sample was not surprising, as it is logical that the heating process would have disabled the enzyme. However, the results from the raw sample trials are suspicious. We discussed these data with Dr. Muraleedharan Nair of the Plant and Soil Toxicology Department at Michigan State University , and he suggested that we might have used too much catechol. Therefore, future experiments could look at the effects of varying the amount catechol used in testing a sample for PPO.

In addition to temperature effects, we predicted the pH of the boiled sample would be higher than that of the raw sample, and thereby would affect the functioning of the PPO. We found no pH difference between the raw and boiled samples however (Table 6). Based on this result, we are unable to explain the lack of PPO in terms of pH. There may have been a slight difference in the pH levels, as we were limited to the precision of pH paper. Future investigations on this topic should utilize a digital pH meter to increase accuracy and precision

Lastly, we took advantage of the Bradford Assay (Khra et. Al., 2003) to determine the concentration of protein in our raw and boiled tomato samples. Our research team predicted we would find a greater protein concentration in the raw sample. Our prediction was supported by our data. We found a greater protein concentration in the raw tomato sample by 0.028 milligrams of protein per gram of tomato (Table 5). This finding is intuitively logical. One would expect the process of boiling to denature some amount of the protein initially present (in the boiled tomato) prior to boiling. For a more precise protein concentration value representative of a particular tomato variety, a larger number of tomatoes should be used in the future.

Because the enzyme test was inconclusive, we based our decision of which, raw or boiled, was healthier (for the protein experiment alone) on the protein concentration data only. Thus, we have concluded that the raw tomato, with a greater protein concentration, would be the more nutritious and healthier choice.

In conclusion, we found that the raw tomatoes sampled contained more carbohydrates (by visual estimation), lycopene, and protein. Despite published research that suggests that boiled tomatoes are healthier than raw tomatoes, our data suggest otherwise. It is important to keep in mind that we only used two tomatoes for each experiment. The results are therefore only representative of those two tomatoes. In order to achieve results that could have a broader application, we should have used more tomatoes for each experiment.

1 Dr. Muraleedharan Nair, Plant and Soil Toxicology, Michigan State University

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to give our sincere gratitude Dr. Muraleedharan Nair for allowing us to use his labs, and providing support with our research. Also, Dr. Jayraj Francis spent many hours in Dr. Nair's laboratory with us helping with the equipment and running of the experiments.