The Buffers

(Jaime Engelhart, Cara DeSanto, Lauren Walker, & Chas Pudrith)

Here are our theories on...

A Comparison Citrus sinensis Rind & Flesh By

Quantitative Analysis

Abstract:

Our intention in this lab was

to prove the idea that the rind of the orange may contain nutrients, but not in

a substantial form when compared to the flesh. This was done with a sugar, photosynthetic, and enzyme lab.

The

sugar lab included Benedict’s, Barfoed’s, Selavinoff’s, Bial’s and Iodine

tests. The results indicated the presence of aldoses and a lack of

starches. The results also

indicated that the flesh had aldehydes and the rinds did not. Monsaccharides were also found only in

the rind while only the flesh had furanose rings. This proved that while the rind had some sugars they were

not of substantial value.

The photosynthetic lab included a paper

chromatography and an absorption spectrum test. The paper test indicated that both the flesh and the rind

had an Rf value of 1. This

indicated the presence of xanthophyll.

With the spectrophotometer, we measured the absorbencies of the rind and

the flesh at various wavelengths and received no information.

The enzyme lab included a pH

test, 2 types of catechol tests, and a taste test. The flesh had a higher pH than the rind. The first test measured the change in

absorbency. The second test was

for a color change when placed directly on the flesh and rind. Both of those test came back negative

implying the lack of PPO and we were unable to conclude anything from these

tests. In the taste test, the flesh received 3 of 4 stars and the rind received

only 2.

Figures:

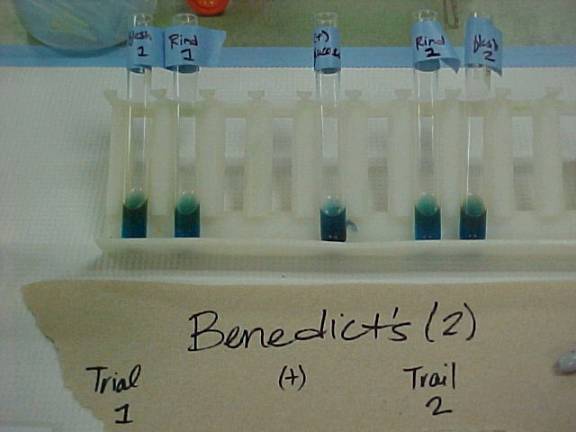

This is a picture of our results from the Benedicts test, the first of 5 sugar

tests. (From left: Flesh 1, Rind 1, Positive Glucose

Control, Rind 2, Flesh 2) Although

it is difficult to notice, there is a red copper precipitate that has formed in

the two flesh test tubes and the positive control. Although a reaction did occur with the rind solution, there

still was not a copper precipitate, therefore the rind tested negative.

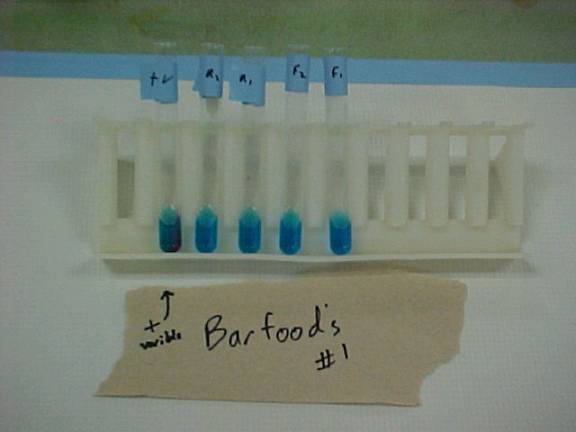

This is a picture of Barfoed’s test. (From left: Positive Fructose Control, Rind 1, Rind 2, Flesh 1, Flesh

2) In this test determined what

saccarides were present within each orange part. The color change in the positive control can be easily seen,

but the rest of the results are not.

The flesh did not react, but the rind did have a slight color change,

which renders a positive result, it is a monosaccaride.

* Benedict’s and Barfoed’s Assays shown in the above pictures. These are the most relevant figures we found for our experiment. This is because from information researched, more energy is given off over time in the flesh since it contained polysaccharides as shown in the results of these tests; therefore, the flesh of the orange has proven to be more nutritious than the rind. *

Discussion:

We based our experiment on the simple question: Does the rind

contain any nutritional value? Once

this question was asked a secondary question followed: If it does have some

nutritional value how does it compare to the flesh of the orange? Should people

continue to throw out the rind of the orange without any thought? We hypothesized that while the rind of

the orange may have some trace amounts of nutritional value, there would be no

substantial benefit of eating the entire orange, rind included. After careful experimentation we were

able to confirm our hypothesis finding that the nutritional value in the orange

was too small to be of substantial value when compared to the flesh.

The

first set of experiments we conducted were to investigate the presence of

specific carbohydrates and their traits. The basis and structure of this lab

closely follows the procedures found in our Laboratory Course Pack. If you refer to Table 1, you will see

the experiments performed and each experiment’s results for the flesh, the rind

and our positive control. Stock

solutions of both the rind and the flesh were blended daily and can be seen in

Figure 1. In each test a given

substance was also tested on, this particular carbohydrate had been tested

prior to the lab and known to have a positive result. This allowed us a standard to hold our data up to, also

indicating that the test was performed properly. The first test we used Benedict’s reagent. This is used to determine if there are

free aldehyde or ketone groups. We

tested both the flesh and the rind twice and found that for each of the two

flesh samples came out positive while the rind samples were both negative. The flesh’s positive results indicated

the presence of reducing sugars.

This is indicated in Figure 2 where a red precipitate can be seen. The reduction of carbohydrates is very

important. If a chain cannot be

easily broken down and digested, it cannot be used as a source for energy. The results of Benedict’s Reagent

helped to confirm our hypothesis when the flesh tested positive for the

reducing sugars.

The next test was executed using Barfoed’s solution, which

indicated the presence of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and

polysaccharides. In the flesh of

the orange the test both of the results came back negative, while the rind

samples tested positive for monosaccharides. The results of this test where there is a slight color

change can be seen in Figure 3.

The presence of the monosaccharides in the rind leads to the assumption

that only simple carbohydrate are to be found in the rind. A diet less in simple carbohydrates is

recommended since they can be quickly broken with very few lasting

benefits. Barfoed’s solution also

supported our hypothesis that the nutritional value found in the rind is

insignificant when compared to the flesh.

Then we used Selivanoff’s reagent to see whether or not these two

parts contained ketoses and aldoses.

Since both the rind and flesh samples resulted in a positive test for

the presence of aldoses we were unable to conclude which one might have been

healthier. These results can be

seen in Figure 4. With Bial’s we

were able to determine if furanoses were present. The flesh samples came out negative while the rind samples

were both positive. We were not expecting results like this. The five carbon ring, commonly referred

to as furanose, was found only in the rind and is an important contributor in

the production of energy. The

slight variation in color can be noted in Figure 5. These results negate our hypothesis. We were unable to find the presence of

any starches in either the rind or the pulp. Since the both came back negative, our results were

inconclusive for this particular test.

We also used Iodine to test for the presence of starches but both tests

for the rind and the flesh came back negative and we were unable to conclude

anything about our hypothesis based on starches alone. The result of these tests can be viewed

in Figure 6.

The second major component we tested our hypothesis with was for the presence of chlorophyll , which is a positive indication for the process of photosynthesis. “This is a very important process and is essential for the existence of life. The formation and maintenance of any living system requires compounds that were formed by transforming: (i) light energy to chemical energy, and (ii) inorganic carbon to organic carbon.” (Course Pack, 71). First we used a chromatogram strip as a way to identify pigments found in the orange and rind. Please refer to Figure 7 to see the results. We were unsuccessful in finding an orange leaf in which we had hoped to compare the levels of chlorophyll a and b and trace the decreasing levels from the leaf to the rind to the flesh. But when the flesh and the rind pigments were compared alone chlorophyll a and b were not found in either. We were only able to conclude that an RH factor of 1 was found both times in each the rind and the flesh. This indicated the presence of only one pigment and that pigment was xanthophyll and is shown in Table 2. Since the oranges we used were of the ripe variety we concluded that since it had reached optimal size the photosynthesis process was no longer necessary in the maturation of the orange. At different stages in growth of the orange it is obvious that chlorophyll is present because the rind has green pigments. Since energy is required to keep producing sugars to add to the growth of the orange photosynthesis creates chlorophyll. This process stops and the presence of the pigments disappears once the orange has matured. Since there was no presence of these two important pigments our results were inconclusive.

A separate test we performed also looking at the important process

of photosynthesis was for the absorption spectrum of the orange vs. its rind.

The levels we found using the spectroscope demonstrated no assistance in

helping us compare the nutritional value of the orange and the rind. This can be seen in both Figures

7 and 8. Since both of our samples do not contain chlorophyll this test was

unable to support or negate or hypothesis. If we could have done this lab again we would have ordered

orange leaves from an orchard or nursery allowing us to verify that

photosynthesis is indeed used in the production of the fruit. We would have also liked to have been

able to test for other possible pigments that might trace the chlorophyll

better from the leaf to the rind to the flesh.

In

our last section we tested for the presence of the enzyme PPO in both the rind

and the flesh. PPO is a enzyme

commonly found in fruit that acts as a catalyst and is responsible for giving

fruit that brownish color when cut and exposed. (Course Pack, 80) The first thing we tested was the pH

level, we found that the pH of the flesh was about 4 indicated that it was

acidic. The rind was also slightly

acidic but only had a pH level of 6. If you look at Figure 10 you can see our results. From this alone we were unable to

conclude anything that related to our original hypothesis. When a slice or the

flesh and rind were coated with 2 drops of catechol solution and monitored over

time there was no change in the color of the orange. This was the first indication that PPO was not found in

either the orange or the rind.

Figure 11 shows the lack of any color change in both the rind and flesh

sample. We decided to do a

second separate test to insure that PPO was not present. When the both the rind and the flesh

were compared using the spectrophotometer. Solutions of both the rind and the flesh were each mixed

with water and catechol. The

transmittance readings of each one were then taken at one-minute

intervals. These results can

be viewed in either Table 4 or Figure 12.

Since there was more of a change in the water we concluded that PPO was

not found in either the orange or the rind and that the small variance in the

transmittance levels was a result of mechanical error. If we were to have had more time and

better equipment we would have like to look that transmittance levels of the

rind and the orange over a greater span of time under much more detail. Chas volunteered himself to do the

taste test. We decided taste is an

important factor in the consumption of food. The taste of the rind explained as somewhat neutral and

bland. Not great, but no horrible

either. Chas’s 4 star rating

system can be seen in Table 5.

Throughout

the course of the lab we ran into several difficulties. Our most important

findings were from the first set of experiments where we found the presence of

different sugars. With the other

sets of experiments it was harder to collect information that would help us

either negate or support our hypothesis. Could we have repeated this test

knowing what we now know there would be several things we would like to

change. When precipitate were

formed in specific tests we should have found ways to measure the amount of

each and compared the two levels.

Quantitative analysis should have been compared as well as

qualitative. Perhaps if we would

have placed the test tubes with precipitates in the centrifuge and then used

the spectrophotometer we would have been able to have quantitative data as well

as qualitative. We were able to

learn a great deal of information both about oranges as well as methods used to

test in a laboratory setting. Through our mistakes we were able to take away a

lesson learned and a better approach to our next similar situation. We would

have like to have performed other tests in which other nutritional factors

like, vitamins, could have been compared.

There were probably numerous human errors that took place on our part

that might have had an effect on our overall results of the experiment. The small amount of lab experience we

had between the four of us was obvious at many points in time. But we believe that our information we

found and provided is correct and using the information we were able to reach a

conclusion. We found that the

experiments we conducted supported our original hypothesis that although the

rind may contain some nutritional value it is insignificant when compared to

the flesh and would not be worth consuming.

J We hope everyone

enjoys our website & have learned something from it!! Have a nice day! J

Email Us: